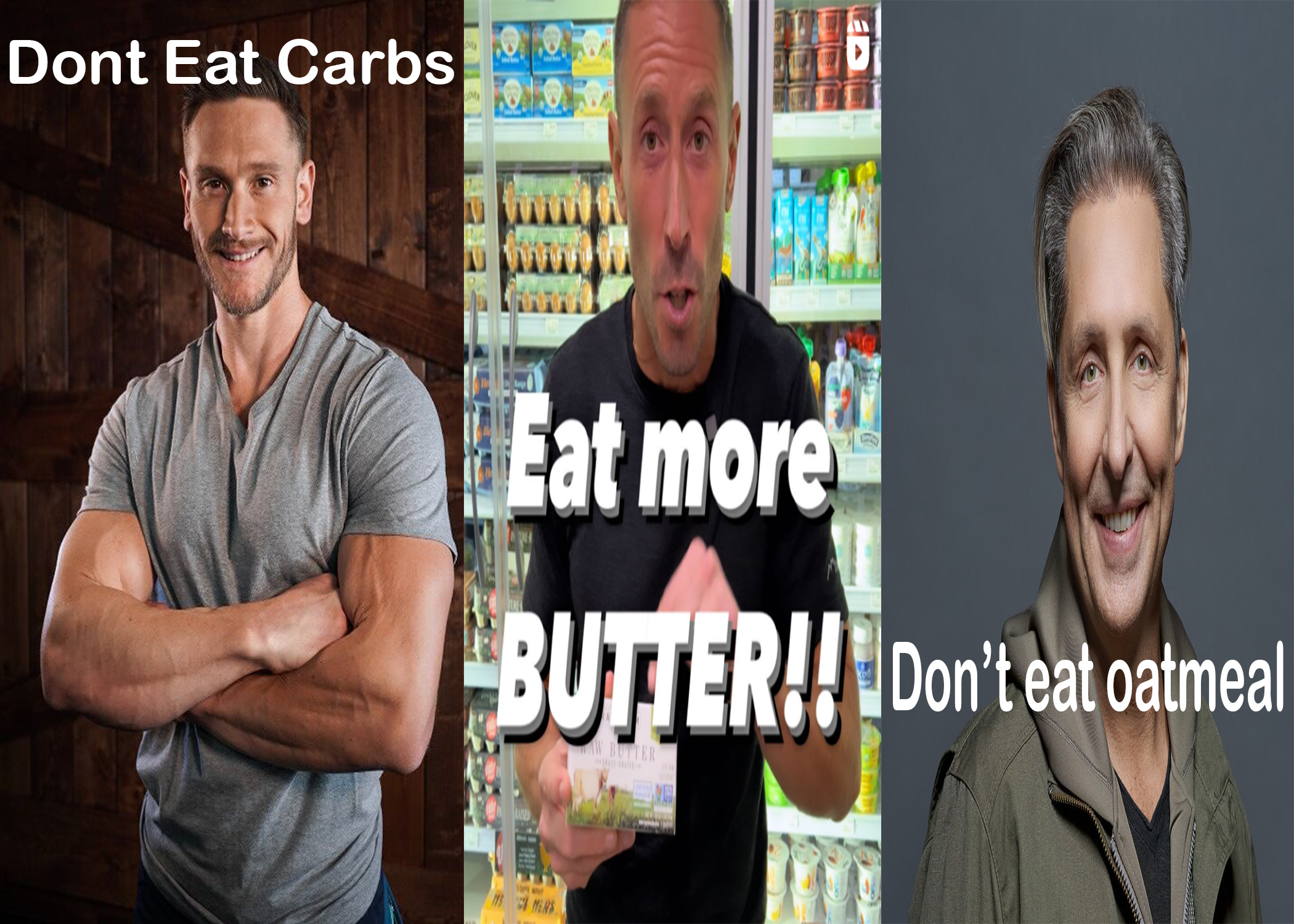

How diet trends work the algorithm

And how people make money

Carnivore diet influencers (like Dr. Shawn Baker, Paul Saladino, Ken Berry, or smaller creators) monetize their audiences through a mix of high-margin digital products, affiliate revenue, and community-building. Below is a breakdown of the exact revenue streams they use, ranked by profitability and prevalence.

- 30-Day Carnivore Challenge $47–$197

- Private Membership Community $29–$99/month

- Meal Plans / Coaching $97–$500

Why it works: One-time creation → infinite sales. Upsells to 1-on-1 coaching ($1k+).

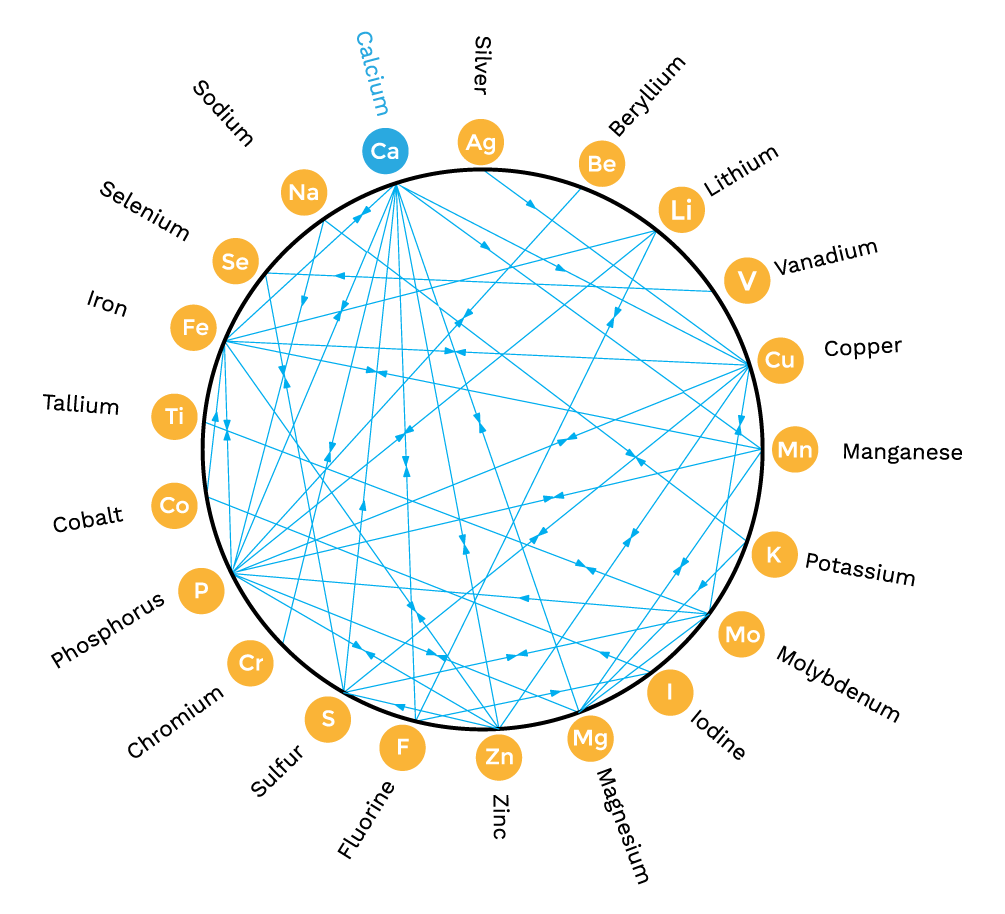

Supplements & Branded Products (30–60% Margin)

They Post Daily for maximum results

- Electrolyte powders (LMNT, Redmond) Affiliate (10–30% commission)

- Grass-fed organ supplements (Heart & Soil) Own brand (Saladino) → 50%+ margin

- Carnivore bars (Epic, Carnivore Crisps) Affiliate or white-label

Books & Audiobooks (Royalty: 10–70%)

Bonus: Book → email list → sell courses.

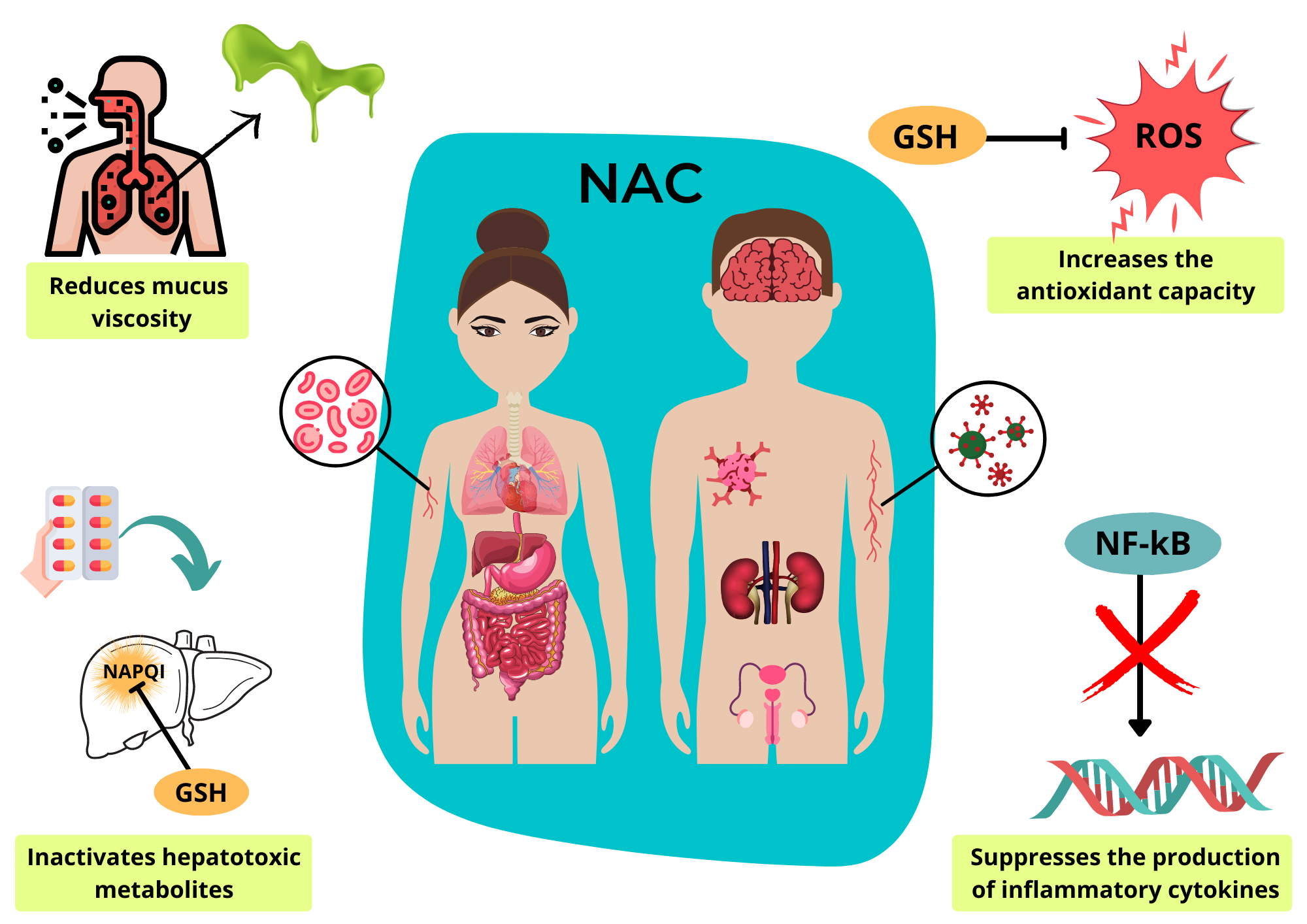

Many of their books are based on weak (or any) actual clinical data. In fact, their references lack any significant support to their claims. This strategy works because we all know that eating lean proteins, healthy fruits and veggies are beneficial for health, but if you can tell me that I can eat fatty pieces of steak, butter and red meat all day and be healthy…. Then I’m sold.

- Self-published (Amazon KDP) 70% royalty

- Traditional (e.g., Baker’s The Carnivore Diet) 10–15%

YouTube & Social Media Monetization

Top earners: 500k+ YouTube subs → $5k–$20k/month in ads alone.

But I haven’t given them a dime of my money… how are they making money off me? Easy, you’re watching, liking, and sharing their content. You’re actually providing them with ad revenue. (Don’t forget to subscribe)

- YouTube Ad Revenue $1–$5 per 1,000 views (CPM)

- X (Twitter) Affiliate links in threads

- TikTok/Instagram Brand deals ($1k–$50k/post)

Affiliate Marketing (Passive Income)

Funnel: Video → “My bloodwork improved!” → affiliate link.

- ButcherBox / Crowd Cow $20–$50 per signup

- Amazon (books, air fryers) 1–10%

- Blood testing (InsideTracker) $50–$100 per sale

Consulting / Medical Practices (For MDs)

Caution: Many avoid medical advice to dodge liability → pivot to “education.”

Dr. Ken Berry: Sells Proper Human Diet course + sees patients. He also sells books based on the notion that your doctors are lying to you with a book title, "Lies My Doctor Told Me." Since this just for entertainment or educational purposes only, he avoids liability.

Fear-based marketing: “Plants are toxic!” → sell animal-based alternatives.

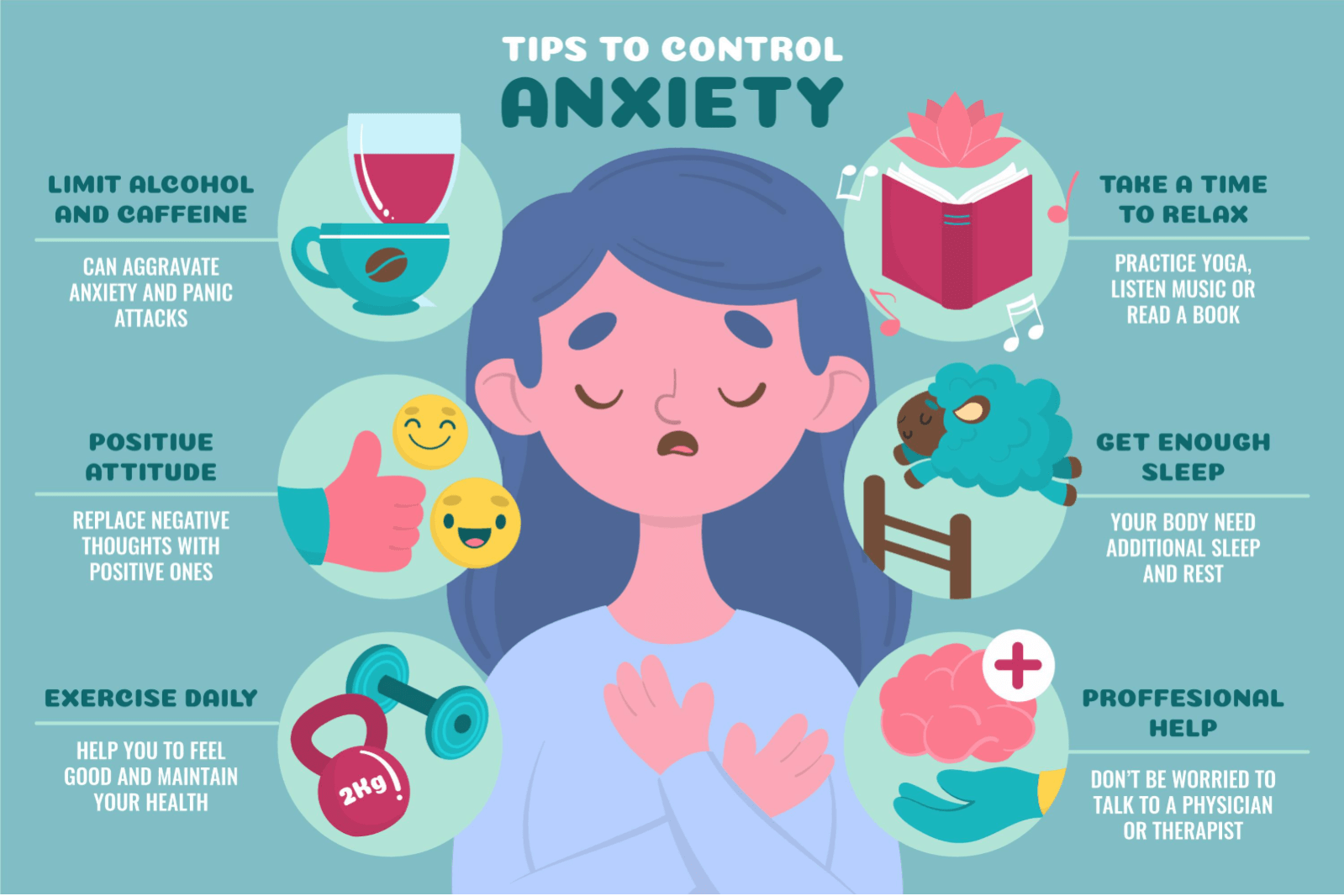

Ditch the lies and follow the science! Your free source of science based literature for health and fitness